Thank you to Ella Van Leer, Blake was able to find out about much of his family’s history later in life. As an orphan he only knew his last name and was told he must be dutch and from possibly from Pennsylvania. Ella did so much research, she was considered the family’s historian and even a genealogist. Her work indirectly helped numerous other families learn about their surnames as a result. Ella was able to trace the Van Leer surname all the back to the original last name Valär and confirm this with the Swiss archives. According to documents provided by the Rhaetian Museum in Chur, it is believed that the Valär family was descended from a Rhaetian nobleman named Valerius. The name was spelled “Vadrain” or “Foedrain” in Romansh. The Valärs lived in and around Prättigau as overseer of castle records or bailiffs. They were essentially one step above peasant or middleclass.

Hans Valär and later “von Lähr” is the earliest ancestor the Van Leer archives can trace back to. Hans and his son are documented in many archery tournaments and is noted as a skilled archer in the Swiss Archives. Hans would later be recruited by Zurich to the Battle of Grandson like many locals.

The family story past down talks about Hans and his son Kaspar who had a tremendous bond. Hans would take his son hunting frequently and desired a simple life in the countryside. However, this is not the case on March 2, 1476. This is a red-letter day in both Swiss and Van Leer history. Hans helped play a crucial role in the battle and is known as the hero of Grandson. He was awarded with treasure and elevated to the “burger” class in the city of Zurich. Hans registered his coat-of-arms in Zurich in 1488. As an immigrant from the Grisons, Hans probably spoke both Romansh and German. The literature available also indicates that Hans was basically a “nobody” before March 2, 1476. The burgers of 1476 represented the middle class of tradesmen and artisans who–along with the nobility–elected city officials and established laws. The Battle of Grandson was a crucial battle with Burgundy.

Prelude

The siege of Grandson and the execution of the garrison, illustration by Johann Stumpf (1548)

In late February 1476, Charles the Bold, also called Charles the Rash, besieged the castle of Grandson, located on the lake of Neuchâtel. Grandson belonged to Charles’ ally Jacques de Savoie, and the place had been brutally taken by the Swiss the previous year. Charles brought a large mercenary army with him together with many heavy cannon, and the Swiss garrison soon feared, after the effectiveness of the bombardment was demonstrated, that they would be killed when their fortress was stormed. The Swiss, under heavy pressure from the canton of Bern, organized an army to come to the garrison’s relief. A boat approached the garrison with the news that an army was coming to its relief, but the vessel was unable to approach the fortress closely for fear that it would be hit by Burgundian cannons. The men in the boat gestured to the defenders in the fortress to inform them that help was on the way, but their gestures were misunderstood, and the garrison decided to surrender.

Execution of the garrison of Grandson

Swiss sources are unanimous in stating that the men only gave up when Charles assured them they would be spared. The historian Panigarola, who was with Charles, claimed that the garrison had thrown themselves on the mercy of the duke, and it was up to his discretion what to do with them. He ordered all 412 men of the garrison to be executed. In a scene Panigarola described as “shocking and horrible” and sure to fill the Swiss with dread, all the victims were led past the tent of Charles on 28 February 1476 and hanged from trees, or drowned in the lake, in an execution that lasted four hours.

Battle of Grandson

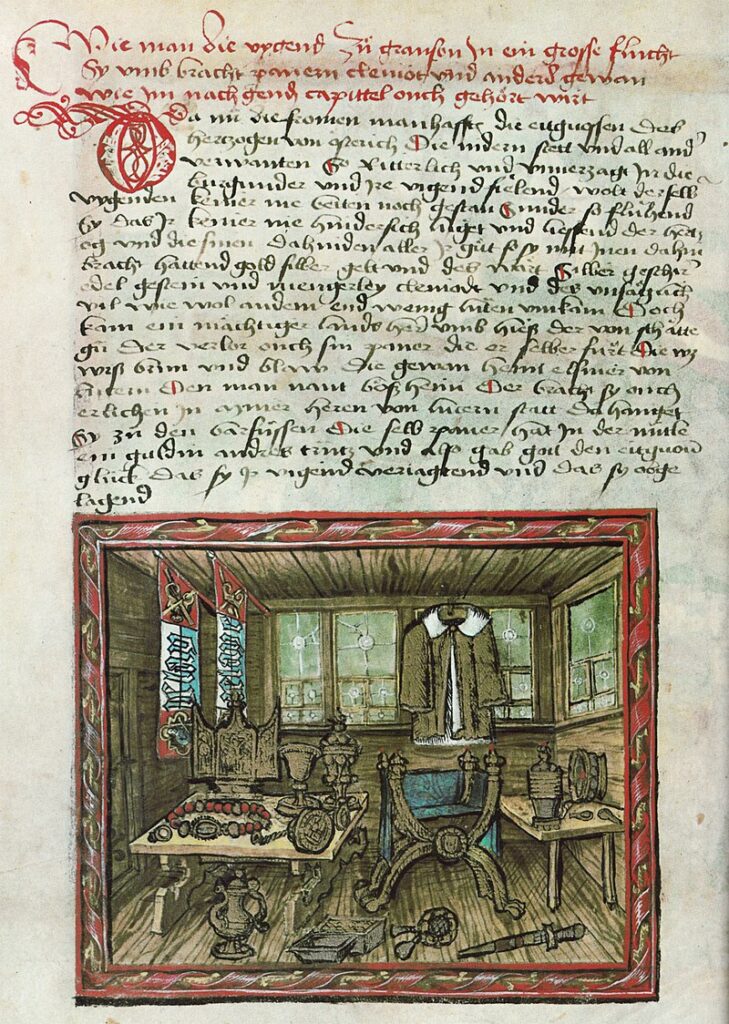

Illustration of the Battle of Grandson by Diebold Schilling the Younger (1513)Pillage of the Burgundian camp after the Battle of Grandson, illustration by Diebold Schilling the Elder (1483)The booty of Grandson put on display in Lucerne, illustration by Diebold Schilling the Younger (1513)

The Swiss had no news of the fate of the garrison and assembled their forces in the hope of lifting the siege. This army numbered a little over 20,000 men without artillery and probably slightly outnumbered the Burgundians. On 2 March 1476 the Swiss army approached the forces of Charles near the town of Concise. The Swiss advanced in three heavy columns, echeloned to the left rear, moving directly into combat without deploying, in typical Swiss fashion.

Poor reconnaissance left Charles uninformed as to the size and deployment of the Swiss, and he believed that the Swiss vanguard was the entire force sent against him. The vanguard, consisting mainly of men from Schwyz, Bern, and Solothurn, realized they would soon be in battle and knelt to pray. When they said three Our Fathers and three Hail Marys, some of the Burgundian army reportedly mistook their actions as a sign of submission. In their zeal, they rode forward shouting, “You will get no mercy; you must all die.”

The Burgundian knights soon surrounded the Swiss vanguard, but then Charles made a serious mistake. After brief skirmishing, Charles ordered his cavalry to pull back so the artillery could reduce the Swiss forces before the attacks were renewed. At this time, the main body of the Swiss emerged from a forest which had hitherto obscured their approach. The Burgundian army, already pulling back, soon became confused when the second, and larger, body of Swiss troops appeared. The speed of the Swiss advance did not give the Burgundians time to make much use of their artillery and missile units. Charles attempted a double envelopment of the leading Swiss column before the other two arrived, but as his troops were caught shifting to make this attack, they caught sight of the other Swiss columns and retreated in panic. The withdrawal soon turned into a rout when the Burgundian army broke ranks and ran. For a time, Charles rode among them shouting orders for them to stop and hitting fleeing soldiers with the flat of his sword. But once started the rout was unstoppable, and Charles was forced to flee as well.

Few casualties were suffered on either side: the Swiss did not have the cavalry necessary to chase the Burgundians far. At insignificant cost to themselves, the Swiss had humiliated the greatest duke in Europe, defeated one of the most feared armies, and taken a most impressive amount of treasure. Charles had the habit of travelling to battles with an array of priceless artifacts as talismans, from carpets belonging to Alexander the Great, to the 55-carat Sancy diamond, and the Three Brothers jewel. All these were looted from his tent by the confederate army, together with his silver bath and ducal seal. The Swiss initially had little idea of the value of their loot. A small surviving part of this fantastic booty is on display in various Swiss museums today, while a few remaining artillery pieces can be seen in the museum of La Neuveville, near Neuchâtel, Switzerland.